Is a higher Tobin's Q ratio a benefit to investors?

Legal scholars say yes. Sensible investors disagree

In an excellent paper by Professor John C. Coffee, Jr. entitled “Law and the Market: The Impact of Enforcement”1 the author argues that the strict enforcement of the 1933 Securities Act and 1934 Securities Exchange Act by the Securities and Exchange Commission is a strength of the U.S. markets encouraging offshore companies to list in the U.S. to realize a lower cost of capital, which some estimate at 70 to 150 basis points. Professor Coffee apparently believes a lower cost of capital (manifested in a higher share price for the same entity arising from securities law enforcement) is something of value to investors. Professor Coffee has a storied career as a leading expert in securities law as the Adolf A. Berle Professor of Law at Columbia Law School and Director on its Center of Corporate Governance. He is widely respected and widely published.

He is nonetheless wrong.

While a lower cost of capital appears desirable for corporations, it is inimical to the returns enjoyed by shareholders of those corporations. The cost of capital is what corporations pay when they raise money which typically is limited to initial public offerings (IPO’s) and the occasional follow on secondary offering to fund expansion. It is also the return that shareholders receive for risking their money in the shares of the corporation. For companies which no longer have to raise money from public investors (like Apple or Microsoft, for example) the cost of capital is largely irrelevant to the corporation. It matters to shareholders. It is tautalogical that a lower cost of capital compels a lower return which is the inverse of the cost of capital.

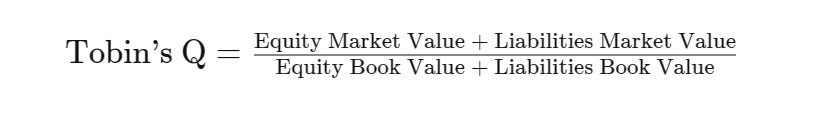

Tobin’s Q ratio is an attempt to measure the market value of an issuer’s securities as a ratio of the replacement value of its operating assets. Since replacement value is difficult to measure, a simplified version of Tobin’s Q is the market value of those securities divided by their aggregate book value.

It is well-established that investors in companies with shares exhibiting a high book value to market value ratios outperform market averages, but that ratio - book value to market value - is the inverse of Tobin’s Q. That insight is so profound Nobel laureate Eugene Fama modified his capital asset pricing model (CAPM) to include a factor for book value to market value for shares being valued.

The actors who benefit from a lower cost of capital are intermediaries who earn fees and commissions based on trading volumes, exchanges that charge fees based on market capitalization, and asset managers who are paid a percentage of assets under management (AUM’s). While these third parties to the corporation benefit, ordinary investors whose money is at risk receive a lower return.

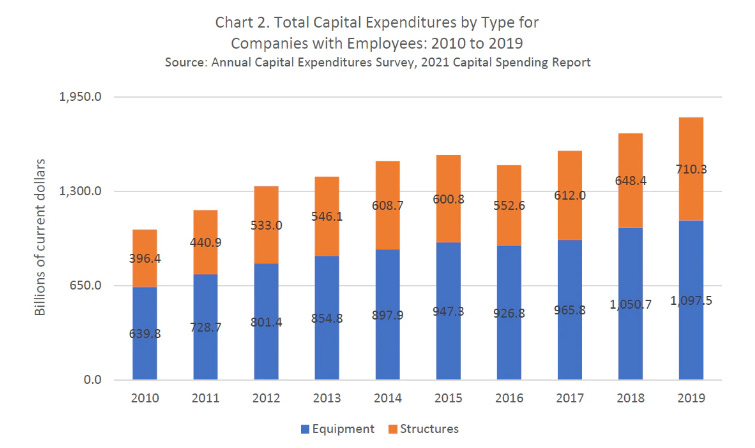

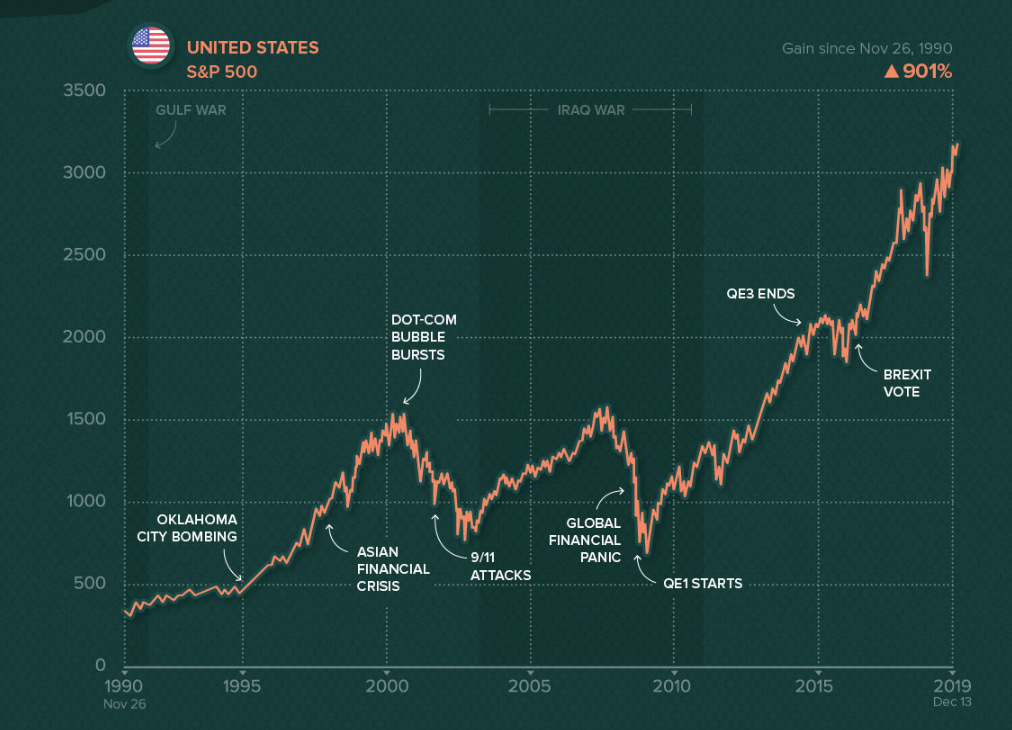

Higher costs of capital play an important role in ensuring that risky projects are subjected to a sufficient hurdle rate that capital is not squandered on low return, high risk adventures. The central bank’s experiment with Quantitative Easing (QE) which drove down interest rates and lowered the cost of capital for most public companies saw a modest rise in capital spending but the rise was a fraction of the $4 trillion spent on QE. The QE spending originated as a reponse to the global financial crisis (GFC) and had a significant role in the economic recovery through 2012 when recovery began to stall. From that point forward, American capital spending rose in line with Gross Domestic Product. What QE did accomplish was to push down interest rates inflating asset prices and driving stock market multiples higher.

Combined with loose fiscal policy, QE also triggered a rise in inflation. QE ended in 2022 followed by efforts to curb inflation including Quantitative Tightening (QT) and high central bank interest rates. he average return on equities (based on the S&P as proxy) during the QE period from 2010 to 2022 was about 10%, not far from the long term average return on stocks generally.

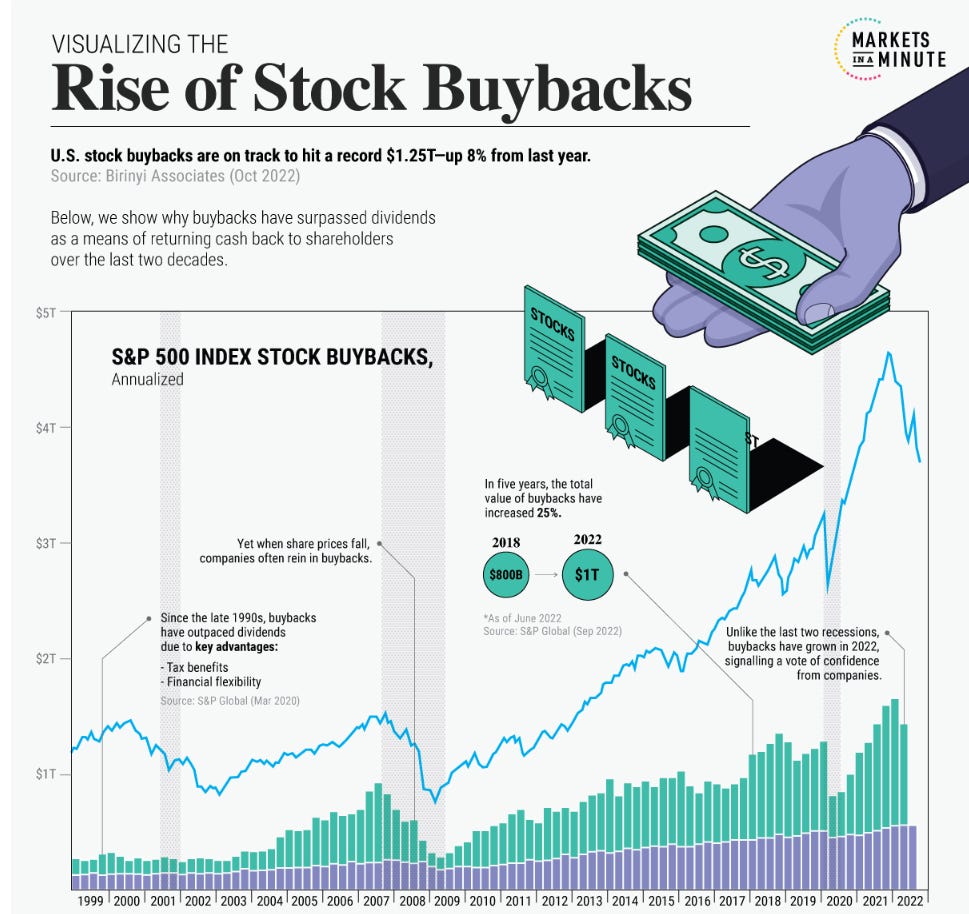

Rather than fuel economic expansion, the lower cost of capital fueled by QE saw a dramatic increase in stock buybacks, the reverse of higher capital formation.

The argument that stronger and more effective enforcement of securities laws manifests itself in a lower cost of capital and that the lower cost of capital in turn contributes to stronger economic growth is not supported by the empirical data. The lower cost of capital compelled by QE simply saw more stock buybacks and a dramatic rise in stock prices fueled by artificially low interest rates.

On the surface, it appears that investors benefited from QE but did they? Those who held shares at the outset of QE benefited from the ability to sell those shares to others at the inflated prices QE causes. The buyers of those shares suffered lower streams of dividends to the extent that the rise in share prices outpaced the rise in net earnings and in parallel dividend streams.

We are now entering a period of QT and rising interest rates which promises to reverse that process with painful results for those who bought into the market believing the upward momentum would be an enduring trend. Asset managers earned higher fees. Intermediaries saw higher commissions. The U.S. treasury collected more capital gains taxes from those wise enough to take profits. And the “buy and hold” investors were able to brag at cocktail parties about the “gains” on their portfolios.

Only time will tell if those paper gains translate into real increases in wealth. I am not optimistic since we are now in the early stages of unwinding QE with QT along with higher central bank rates and the carnage I foresee in stock prices is on the road ahead and not in the rear view mirror. One canary in this coal mine is the recent performance of the $536 billion Canada Pension Plan portfolio returned a meager 1.3% for the year ended March 31, 20232 and which for the first quarter of fiscal 2023 posted a loss of $16 billion or equal to a loss of 4.2% of its assets under management.

If listing on a U.S. exchange does not impact the operating assets of a company, sales and net income will be unaffected yet the returns to investors will be less since they will have to pay a higher price for their interest in the same income stream. By “returns” I mean the stream of cash distributions emanating from their holdings, not the “notional value” including the trading prices of the stocks, which has been an unreliable source of value by inspection of the historic swings in the indices.

The 70 to 150 basis point drop in the company’s cost of capital Professor Coffee suggests as the prize for stronger securities law enforement practices merely results in a lower return to investors. For the S&P average for many years the return to shareholders has hovered around 10 percent. A drop of 70 to 150 basis points would lower that return to 8.5% to 9.3%. Over a 30 year investment period (a reasonable proxy for pension funds and other long term investors) that difference translates into a material loss of actual value.

$10,000 invested at 10% for 30 years is worth $174,494

$10,000 invested at 8.5% for 30 years is worth $115, 582, thirty four percent less.

That is a lot less money to pay pensions.

The investment industry comprises parties whose income comes at the expense of investors who pay fees, commissions, etc. for advisory and portfolio management services. Those services are essential for many investors but are not free. Rather, they are parastical to investment outcomes.

Legal experts like Dr. Coffee have bought into the charade that higher stock prices are a reasonable objective, when the only sensible objective is higher streams of net income which will result in higher streams of dividends and interest paid to investors. Higher stock prices comprise actual increases in wealth only when supported by higher levels of sales and net income. Gains from artificially higher stock prices require an investor to sell, pay transaction fees, suffer tax consequences and then find another investment at least as attractive as the one sold (adjusted for those selling costs and the costs of making a new investment). Each gain by one investor in secondary trading is offset by a loss by another investor and as a group all investors lose money to transaction costs and taxes.

Theories that a lower cost of capital benefits investors is not only ill-founded but have seen legislative bodies and administrative agents like the SEC impose laws and regulations on markets that pretend higher trading prices are valuable but set out to deter fraud by insiders (a worthwile objective) to ensure confidence in markets. But public prosecutions and private class actions are typically settled by defendant issuers or their insurers for the benefit of one group of innocent investors at the expense of another group of innocent investors, since the funds that pay the settlements are paid to investors on whose behalf the claim was brought at the expense of the other innocent shareholders through their interest in the corporate defendant to those actions who (directly or through insurance pays) the settlement. In most cases, the settlement indemnifies the corporate insiders who negotiated the settlement, so the real culprits benefit while ordinary investors lose out.

This is a perverse outcome. Securities Regulators exist to protect investors but act to benefit third parties such as attorneys, accountants, financial intermediaries and the culpable corporate insiders whose conduct gave rise to the successful claim but who were not required to contribute to the settlement or otherwise punished for their role in the offensive acts. It is time for economists who study markets and for legal experts who study the evolution of jurisprudence and advise legislators in enacting laws to come together to put Humpty Dumpty together again and reform securities legislation to protect investors rather than to benefit intermediaries and corporate insiders at their expense.

Corporate insiders of issuers found to have released false or misleading disclosure to spur a rise in stock prices and benefit through stock options, RSU’s, etc. deserve not only prison time to reflect on their misdeeds but also disgorgement or forfeiture of any gains and fines that are high enough to form an actual deterrent to criminal behaviour. Those found guilty of defalcation deserve prison time and orders for restitution the corporation of the amounts taken. All involved in criminal misuse of corporate powers should be banned from acting as an officer or director of any reporting issuer for at least five years if not for life. The United States regulators lead the world in this regard, with substantially greater numbers of prosecutions of insider trading and fraud crimes, hundreds of insiders jailed and fined, and dozens of insiders banned from employment in public companies.3 The rest of the world needs to follow suit in my opinion.

John Coffee, The Impact of Enforcement, University of Pennsylvania Law Review, December 2007, Volume 156 No. 2 pages 229-311

Coffee, page 275.