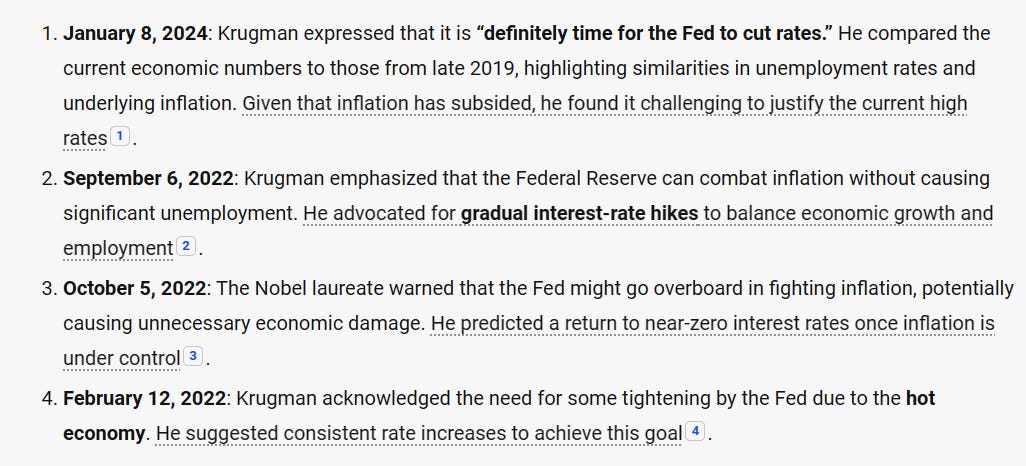

For the past year or so, the airwaves are chock full of talking heads including Harvard economist Larry Summers and Nobel laureate Paul Krugman giving opinions on whether the Fed’s policy rate will rise or fall, and if it falls, how many rate “cuts” will take place and when. Krugman seems schizophrenic on the subject, apparently dedicated to the view that minor changes in interest rates determine economic outcomes:

Krugman should have retired in the glow of his Nobel prize and avoided looking foolish ever since.

Larry Summers makes more sense, but still overstates the importance of rate policy in my opinion. Summers believes that the Fed’s estimate of the neutral policy rate is too low. He argues that the actual neutral interest rate far exceeds the preferred 2.5%, potentially leading to misjudgments about the restrictiveness of its monetary policy. Despite recent easing of financial conditions, inflation expectations remain persistently above the Federal Reserve’s target, creating a complex economic landscape for the Fed to navigate12.

I think Summers is one of the best economists of recent years, but think speculating on Fed policy rates is not that useful. It is hard for me to imagine a more wasteful way for two such brilliant minds to squander their time. The debate always turns on a question of “what is the neutral rate?”.

The neutral rate dates back to 1898 when economist Knut Wicksell defined it as the interest rate that would bring an economy to aggregate price equilibrium if all lending were done without reference to money. John Maynard Keynes, the father of “Keynsian” economics, called it the natural rate. Today economists think of the neutral rate as the real Fed funds rate equal to the nominal Fed funds rate less an adjustment for expected inflation.

The problem is that whatever it might be, it can only be assessed retrospectively. Many countries have enjoyed full employment for periods of very high interest rates relative to today’s rate. In 1983 the Bank of Canada rate was 13.5% in January and fell to 12.5% in November. Real GDP growth in 1983 was a blistering 5.9%. Does anyone think a 13.5% Bank of Canada rate was “stimulative” or “neutral”? The Bank of Canada thought it was “restrictive”. If it was, it was with a serious lag.

Sell-side firms and their traders and portfolio managers and advisers love to promote the concept that they have insight into the Fed’s rate decisions, and call for bullish or bearish markets as if the level of interest rates was the determining factor in whether investors should buy or sell stocks. In June of 1982, the Toronto Stock Exchange (TSX) index was about 1,500 and by December of 1985 it almost doubled to 2,900. Was the double digit interest rate of 1983 an indicator of a stock market boom?

Economists and bankers seem to think tinkering with the Fed policy rate or the Bank of Canada rate is the driving force behind economic growth or stock market trends. Bullshit. While the central bankers are “tinkers” and try to “tailor” their policy rates to the political climate and a belief that their rate decisons are the primary factor in determining economic growth, reality is that those decisions are secondary to global forces and corporate profits that underly stock market performance, with interest rates an also-ran factor. Global wars, energy prices, trade wars, and outsourcing of production to low wage countries have had more effect on the economy than interest rates at almost every point in time in history since the beginning of the 20th century.

Traders bet on stocks, but every gain comes at the expense of another traders’ loss. Portfolio managers charge fees for assets under management, reducing returns to the clients who actually own the securities they “manage”. Sell-side analysts’ and advisors’ compensation is based on the amount of trading commissions and transaction fees they generate for the entities that employ them, not the success or failure of their clients portfolios to earn reasonable returns. To fuel fear of loss, they define “risk” as volatility when in fact “risk” is the possibility of loss or of an inadequate return, and volatility is irrelevant to everything but option valuation.

The theory that interest rates are the control knob of the economy has more substance than the theory that CO2 causes climate change, but not much. What they have in common is material errors: an oversimplification of how the world works in the case of interest rate theory and an outright abandonment of the laws of physics in the case of climate change.

We are in a world where productivity is likely the key to ongoing economic growth, and the emergence of artificial intelligence and related innovations will have more impact than Fed policies. World energy prices and energy supply is a greater driver of economic outcomes than Fed policies. Both point to stronger growth if world leaders abandon their climate nonsense.

Of course, there is risk. A third world war seems possible with a belligerent Russia and Iran, a China growing more powerful every day, and a mercurial leader of nuclear armed North Korea. NATO is weak with Biden afraid to curb Russia in Ukraine and likely just as frightened of the possible annexation of Taiwan by China. Biden looks as weak as Neville Chamberlain in the 1930’s and there is no Churchill on the horizon in America or Europe. War is unlikely but is a tail risk to remember.

Do yourself a favour. Make your investment decisions based on fundamental value, eschew trading, and stay away from advisors, and you might accumulate enough wealth to retire.