Chapter One: Efficient investing in Inefficient Markets

The Efficient Market Hypothesis dismantled

Eugene Fama became famous and won the Nobel Prize in Economics for his publication of the theory that stock markets efficiently priced secondary securities with the price on any given day reflecting a consensus of investors taking into account all information in the public domain. Fama’s 1970 book “Efficient Capital Markets: A Review of Theory and Empirical Work” was the foundation for the Efficient Market Hypothessis (EMH) that became the mainstay of financial theory for decades.

Fama’s Nobel Prize was paralleled by Nobel Prizes in Economics for Harry Markowitz, James Merton, Merton Miller, Franco Modigliani, William Sharpe and Myron Scholes who contributed to the concept of efficient markets, embraced and advanced the EMH applying it to portfolio management and securities valuation. Sharpe developed the widely used Capital Asset Pricing Model (CAPM) which valued securities based on their relative risks with the metric “Beta” being the measure of risk - a statistically derived measure of the degree to which the price of a given stock moved in relation to the market averages. Harry Markowitz undoubtedly influenced Eugene Fama’s work with Markowitz’s 1952 paper which asserted that for a given level of risk investors could optimize returns on a portfolio through diversification.

Virtually every student of economics and finance and every student studying to earn a Master’s Degree in Business Administration (MBA) found the works of these Nobel laureates mandatory reading. I did, when I completed my MBA at University of Western Ontario in 1976. The theories were elegant, simplified complex issues of price discovery and valuation, and gained widespread acceptance. They were also wrong.

The flaw in the theories was the idea that investors could not outperform markets for sustained periods - a virtual impossibility according to Fama - owing to the efficiency of the market in pricing stocks. The underlying but unstated assumption was that “outperforming the market” meant choosing stocks that rose in price more than the market averages on a systematic basis. But “outperforming” the market is better defined as earning returns on investment greater than those evident in market averages or large and well diversified portfolios such as the Standard & Poor’s 500 Industrials. So defined, it is almost trivial to “outperform” the market if investors realize that higher share prices do not comprise “performance” but are in reality inimical to higher returns.

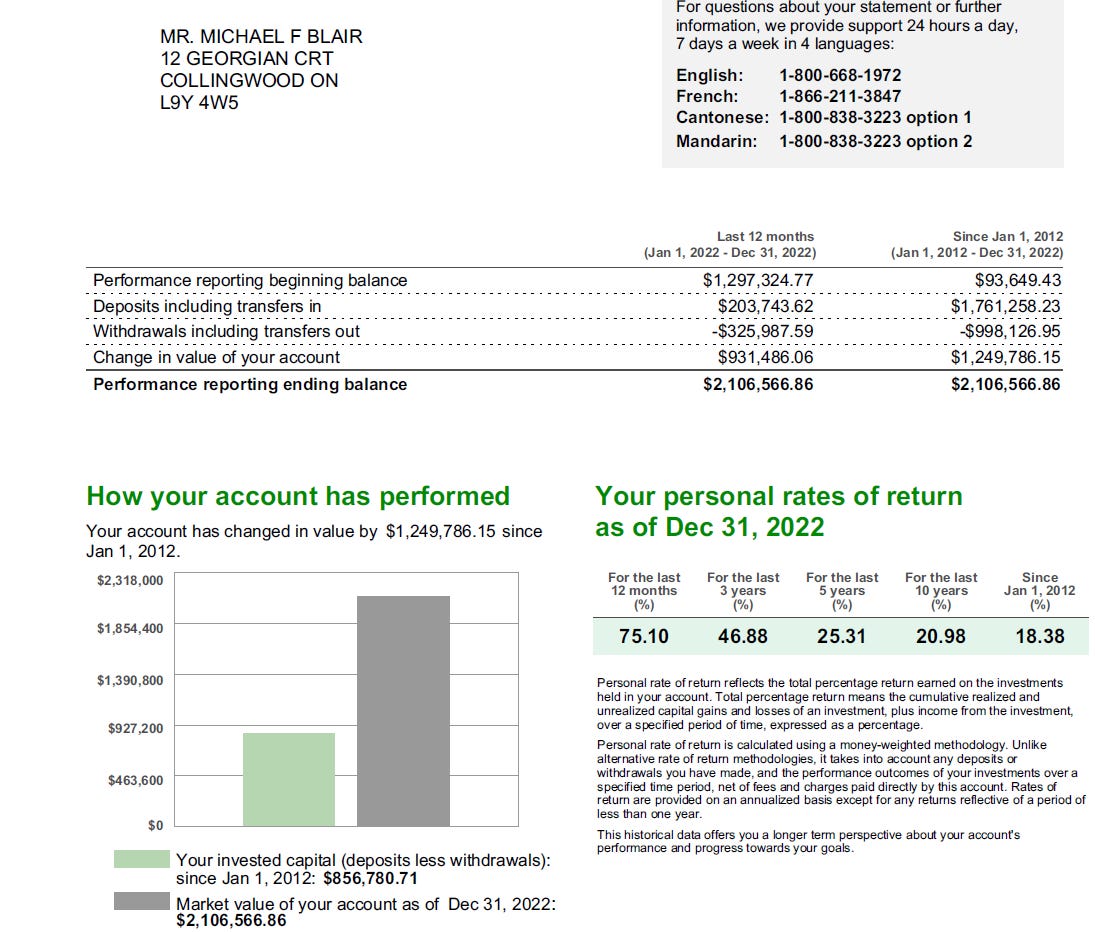

It is tautalogical to say that higher stock prices compel lower returns to investors - if you pay more for a share of a future stream of dividends you necessarily earn a lower rate of return. In this book I will develop an alternative theory of investing and markets that recognizes the reality of that statement. I will preface future chapters by simply disclosing that my own performance in the stock market has consistently outperformed the market averages since I graduated with my MBA and continues to do so. Here is an image of from the fees and returns report from TD Waterhouse on my investment account at that institution for the past decade.

My returns have been more than double the market averages. This book hopes to explain why. I will publish the first few chapters one at a time on Substack.