Are stock markets are grossly over valued and is a crash coming?

Biden policies contribute to the risks of a collapse

Business valuation theories have been the underpinning of a litany of Nobel Prize winning ideas. Names like Eugene Fama, Harry Markowitz, Merton Miller, Franco Modigliani, Robert Shiller, Daniel Kannehman, Myron Scholes, Fischer

Black, James Merton and Richard Thaler have all contributed to the foundation of modern valuation theories which explain much of the movement of stock and bond prices for the past century or so. None of them explain the manias that lead to extremely low or extremely high valuations, but some are useful in knowing when those extremes are present and a major move is likely if not imminent.

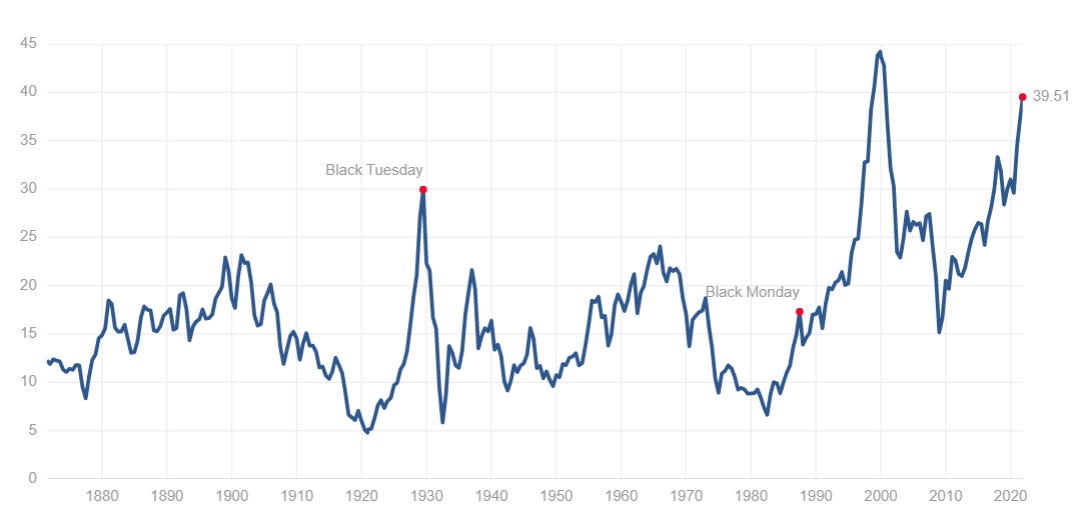

Bob Shiller’s contribution is worth a comment. Shiller developed the cyclically adjusted price earnings multiple (CAPE) as a mechanism for comparing market valuations to historic norms and directionally helping investors understand whether markets are overvalued or undervalued. At present, the CAPE ratio is close to an all time high.

The most notorious market crashes all followed peaks of the Shiller index. For those interested in the statistics, the all time peak ratio was 44.19 in December 1999 and the all time low was 4.78 in December 1920, with a mean of 16.89 and a median of 15.86.

In a typical slow economic growth scenario, the return on a market investment is the reciprocal of the price to earnings multiple. Over decades, the market has returned about 7% to investors, more or less the reciprocal of the 15.86 median multiple. Far greater returns are enjoyed by investors who entered the market when multiples were low and sharp losses were suffered by those who invested when multiples were high. An oft cited rule of thumb is that the market is fairly valued at a multiple of 20 less the inflation rate. With inflation today running at 6.2% in the United States, a market multiple of 13.8 times is expected.

Richard Thaler is a behavioral economist who demonstrated a unique characteristic of investors - they tend to over react to bad news and under appreciate positive trends. His conclusion was that investors could outperform the market averages by purchasing the worst performers on the S&P index and holding those for at least three years.

Eugene Fama, one of the advocates of the “efficient market” hypothesis, noted that two classes of stocks outperformed market averages over time - those with small market capitalizations (as a group) and those with high book value to market price ratios. He modified the traditional Capital Asset Pricing Model (CAPM) which values stocks based on Beta (the ratio of their price volatility to the volatility of the market average) to a three factor model which includes not only Beta but also ratios of their relative market capitalization per share and their relative book value to market price per share. His “three factor” model was more accurate than the traditional CAPM approach.

Valuation theories have evolved slowly with each advance winning its author a Nobel prize, it seems.

James Merton, the late Fischer Black and Myron Scholes won their Nobel prize for the development of the Black Scholes model to value stock options, using partial derivatives to demonstrate that an option is a stochastic way to balance risks that a stock will rise in price with the risk it will fall, valuing an option at an indifference point. That advance has been widely accepted and expanded to value “real options” like mining or energy reserves that are proven but not developed creating a “real option” on future commodity prices.

These sophisticated theories are the domain of valuation experts but simpler models are all that are needed to make educated guesses on whether markets are over or under valued, based as much on mathematics as on common sense.

University of Toronto professor Myron Gordon in 1950 developed a simple model of valuation of a dividend paying stock on the theory that the current value is the present value of all future dividends at a “required” rate of return. Although necessarily a simplification, Gordon’s model was nonetheless useful in valuation of steadily growing companies paying out regular dividends. It is also useful in valuing the market as a whole, since the averages smooth out the volatility of any particular stock’s fortunes.

At today’s market prices, the “earnings yield” of the Standard & Poor’s 500 stocks in 3.39% while the “dividend yield” is 1.28%. The “earnings multiple” of those stocks at this moment is approximately 39.3 times, or about triple what the old “rule of thumb” of 20 less the inflation rate would predict. Does that compel a conclusion that stocks are “overvalued”? No. It compels a conclusion that the market is reasonably valued only if the implied growth in earnings justifies a 39.3 times multiple. We can reverse engineer the implied growth rate from the Gordon model by assuming a dividend of $1.28 and a stock price of $3.39 x 39.3 = $133.23 (a proxy for the market) and a “required rate of return” of 7%, more or less the historic norm.

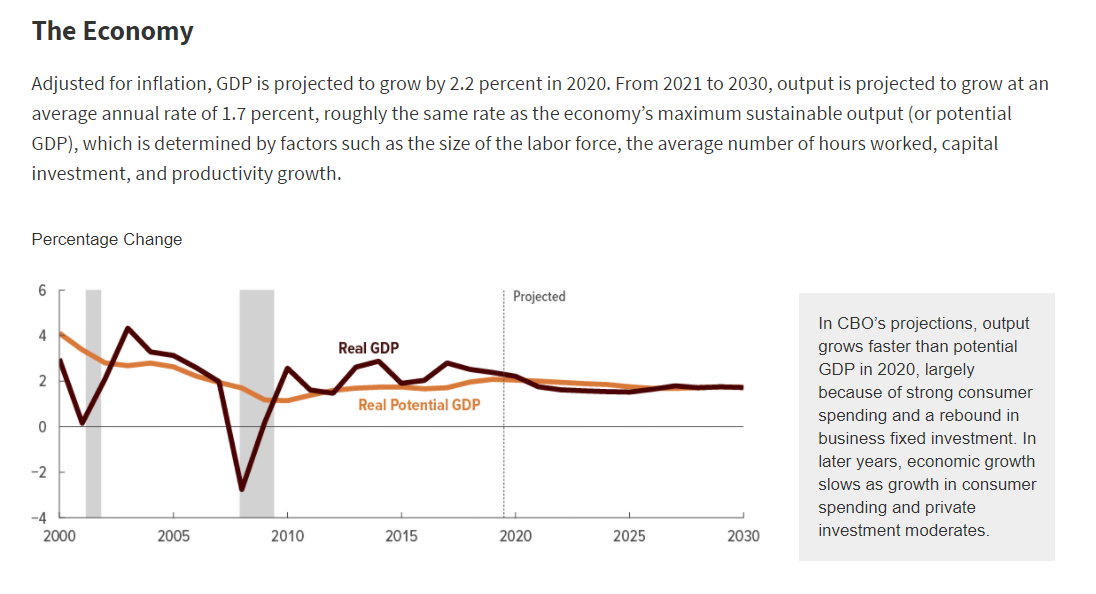

Value = $133.23 = $1.28 divided by (.07- growth rate) which gives a constant growth rate of 6%. That is about triple the economic growth rate projected by the Congressional Budget Office.

There are many forces at work and projecting economic growth or future earnings is more of an art than a science and fraught with risk, but common sense leads me to conclude that markets are due for a major correction or we are about to enter a period of sustained economic growth at levels we have not seen for decades.

In an earlier article, I set out the case for “stagflation” arising from excessive government borrowing and senseless policies that encourage people to leave the workforce both in Canada and the United States. It seems obvious that growth requires people to work and the risks are to the downside.

Market crashes are rare occurences, typically triggered by a single event such as the September 15, 2008 collapse of Lehman Brothers or the November 22, 1963 assassination of President Kennedy. Attempts to ”time” the market are generally futile and smart investors take a cautious approach. In the 1987 market crash of October 19, 1987, billions of dollars of losses were absorbed by investors in a matter of hours. Not everyone lost money.

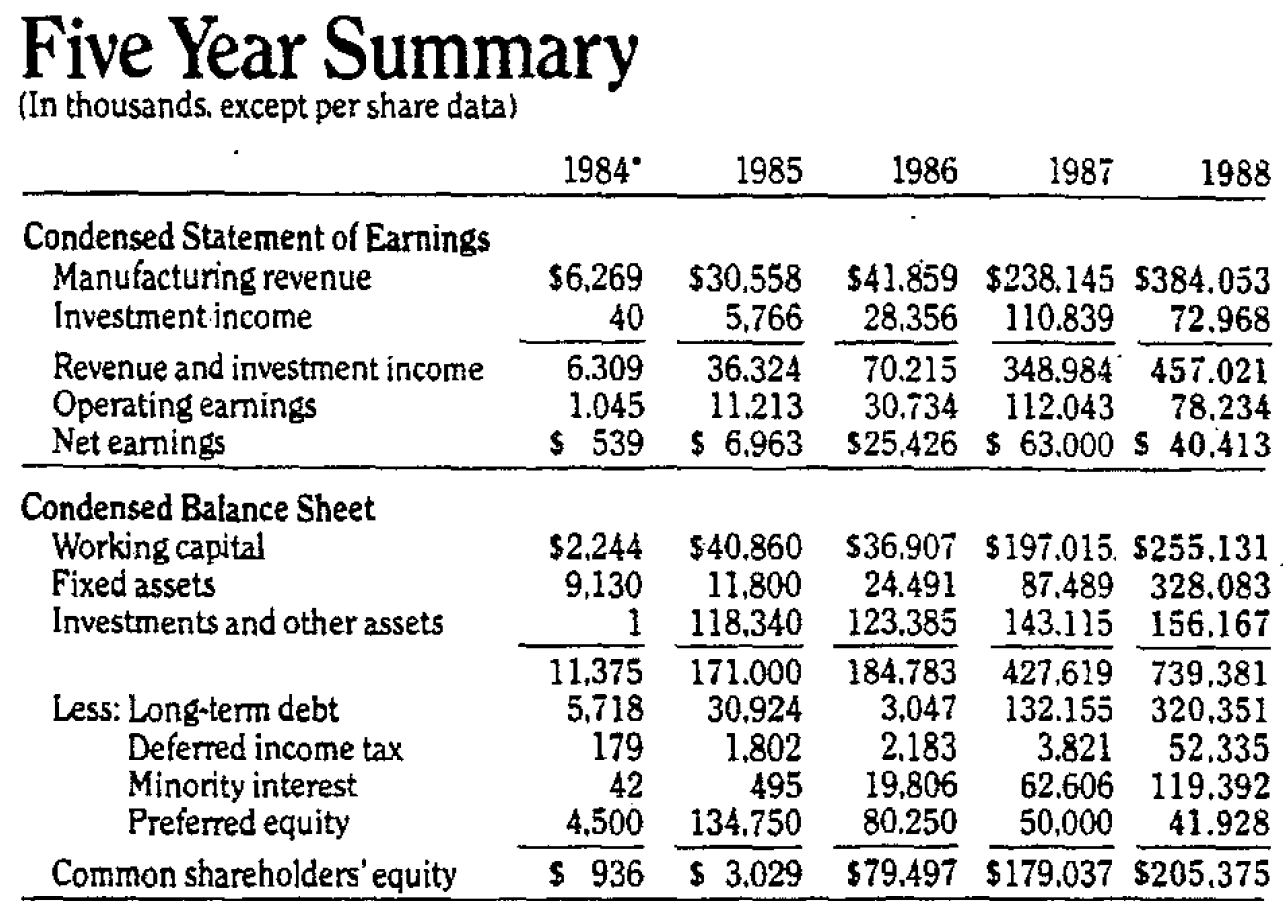

At the time of the 1987 crash, I was President and Chief Executive Officer of The Enfield Corporation Limited (“Enfield”), a company I founded in 1984. Enfield had a portfolio of market investments which I managed, and in 1987 Enfield recorded investment income of $111 million and in 1988 another $73 million on portfolio investments of roughly $150 million in both years.

THE ENFIELD CORPORATION LIMITED

I was prepared for the 1987 market collapse more by luck than good management but Enfield’s portfolio was wisely chosen and investors benefited from my caution.

In today’s market, investors can safely invest in deeply undervalued securities in debt free low cost commodity based companies in mining and energy industries but should avoid companies whose stock prices are discounting unrealistic growth - like Tesla, Amazon, Shopify, Facebook and other market darlings. In a major sell off, these names will be sources of cash for many. It is not a good time to buy on “margin” and it is sensible to have a reasonable cash balance of as much as 30% of your portfolio.

Good luck with your investments.

If I had just 10% of your understanding my portfolio would return more.